It's fitting to write a post in October about horror in Dungeons & Dragons. There has also been some by now not-so-recent discourse on TTRPG Twitter (a truly terrifying place) about the use of horror tropes in gaming and how consent and safety tools play a role in using these elements in games effectively.

Horror has always been inherent to the genre fiction that has inspired and is in turn inspired by D&D. The monsters the characters might encounter in any given game include aliens, demons, devils, ghouls, ghosts, vampire, witches, zombies, and more. It's challenging as a Dungeon Master to describe these creatures and their behaviors in all their visceral detail without evoking some measure of horror or ick in your players.

I want to elicit those reactions, but not every DM does, and not every player wants to experience those feelings. How do we square that?

Fear

Fear in D&D is two-faceted - that which terrifies the characters and that which terrifies the players. Characters can be subjected to magical fear and effects which induce magical madness, but otherwise, characters are only frightened when the players decide they are, which is very rare (in my experience - your mileage may vary). Players can be made uneasy using description and ambience, and can occasionally be frightened by the risk of losing a beloved character or by a particularly nasty mechanic or monster, like undead and their level draining abilities in editions past.

This article on D&D Beyond, published around the time of Van Richten's Guide to Ravenloft and written by the supplement's project lead, is particularly useful in gaining an insight into how the designers of 5th edition view horror and how it should and shouldn't be used in the game, as well as why the genre might be challenging to utilize in D&D. To summarize:

- "D&D’s rules directly oppose building long-term dread...D&D characters steadily get stronger and more versatile, giving them the resources to triumph over ever-greater threats."

- Attempting to make D&D a different game in order to fit it into the horror genre is a bad idea.

- The DM and players are mutually responsible for making a game scary.

- Miscommunications about the tone of a game can ruin the game, i.e., talk to your players about what they're looking to experience and craft a game to match their expectations.

- Frighten characters, not players.

I agree with most of these points, minus the last one, and the prior point to some extent.

D&D is best played as the game is was meant to be played as - if the DM wants to run an adventure similar to one of H.P. Lovecraft's stories, then they should run Call of Cthulhu, not D&D. The rules of D&D make it so that your players are more likely to want to fight a gruesome monster than they are to run away from it. Players are the only ones who should be deciding if their characters are non-magically frightened, so their buy-in is important if the DM wants them to roleplay their characters being scared, and in order to get buy-in the DM needs to set expectations appropriately.

Now, I certainly don't think you should go all Scare Tactics on your players in the middle of a session, but I do think that it's perfectly fine to scare your players. You can do this by creating a playful sense unease at the table - by changing the lighting, playing music, etc. - using gruesome descriptions of fantasy situations and creatures, and by using deadlier-than-recommended monsters in your encounters to threaten their characters.

All of the above can put everyone in the right headspace for a game like Curse of Strahd or anything else in Ravenloft, or even just for a good ol' fashioned delve into a ruin filled with level-draining undead. My preferred brand of horror in D&D is one which causes my players to ask where I came up with something so disturbing, then laugh as they do the predictable thing and fight their way out of the gruesome situation. If I can get them to run away instead, it's a job well done, but I know I'm playing D&D, and that my players are looking to be victorious in most scenarios.

I also don't agree that the DM should cater to their players' expectations when including horror in their games. It's like players submitting a "Chosen One" backstory or a list of desired magic items in Session 0 - it's great to know that a player wants their character to become Luke Skywalker or that their build relies on getting a Holy Avenger at Xth level, but that doesn't mean I'm going to cater to that specifically. Similarly, I'm probably not going to ask my players how they want to be scared and then orchestrate scenarios to scare them in those specific ways, but players should know what kinds of horror are on the table.

As with other horror media, good taste is important. Horror movies which engage solely in torture porn are reviled by all but the most hardcore gore-lovers, and movies which exploit sexual assault to elicit fear are usually alienating for a huge chunk of their potential audience. Not everyone loves slashers and body horror, but they are more widely accepted by mainstream viewers. A DM should make an effort to get an idea of what their players are into, and have the good sense to not be a weirdo or a creep about it.

Consent and Safety Tools

The most important thing a DM can do with their players, especially if the two are unfamiliar with each other, is to set expectations and get consent beforehand. This is pretty easy if the DM is running an adventure module or some other pre-written (especially linear) content. The DM should have at least skimmed the content to get a sense for what all is there, so it's fairly trivial to go through the list and say "We're playing Curse of Strahd. Are you familiar with Dracula? The big bad guy is a vampire lord who preys upon his subjects and is a generic creepy vampire. The people of Ravenloft all have horrible lives and it's very bleak. There are also fiendish hags who eat babies and stuff. We good with all that?"

I find this to be a point of consternation in my own games, which tend to be sandboxes which I loosely build from the ground up as the campaign progresses. I don't know every single thing that's going to come up in one of my games at the first session. The starting town might be dealing with down-on-their luck mercenaries turned to banditry, troublesome fey pranksters, and skeletons who have broken free from their overlord, but by the end of the game the players may have encountered dwarf vampires engaging in ritualistic cannibalism, brain-eating aliens that transform their victims, sorcerous snake men that lay eggs in their mammalian slaves, and Hellraiser demons from the Elemental Plane of Pain who get off on torturing mortals.

Luckily, the DM doesn't need to know everything that will happen in their game in order to make their players aware of what might happen. The DM knows their self (hopefully) and is more aware than anyone else what sensibilities they tend towards in their games. For example, I know that I love body horror and alien weirdness. I love to describe gross transformations and horrific monsters that try to eat your brains or plant their babies into you (more like slaad tadpoles wriggling under your skin and less like...sex stuff). I can easily tell my players up front that I like horror movies (and which ones, or subgenres) and that I like to accentuate the inherent horror of certain D&D monsters in my games.

It also helps to know one's players, and luckily I do. I tend to play with people who are familiar with D&D's tropes, so they're well acquainted with mind flayers, aboleths, hags, and the like. I don't need to preface most of my games with warnings about what might happen to my players' characters. It's worth it for the DM to know if their players are familiar with D&D tropes and monsters, but I wouldn't want to completely spoil it for anyone who hasn't encountered those things, either. Make them aware of the possibilities - don't take them on a guided tour of the Monster Manual.

If the DM knows their players, they also might know what horror tropes might take them out of the game or viscerally upset them, and obviously the DM should avoid those. If DM and players are comfortable with each other, the DM can let their players know that players can talk to the DM at any time about anything that bothers them in-game, whether as a group or privately.

I've never used

Lines and Veils or

X Cards in my own games because my players have always turned down the option, but they are useful tools for players, and I might require their use were I to play with people I was entirely unfamiliar with.

Isn't There Someone You Forgot to Ask? (It's TTRPG Twitter)

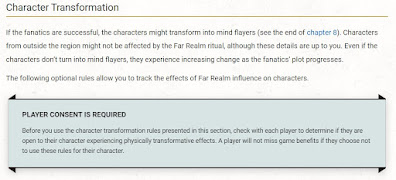

The screenshot above, from

Phandelver and Below: The Shattered Obelisk, made the rounds on the internet and triggered a broader discussion about consent and safety tools in D&D and TTRPGs. At the risk of sounding like some tedious people on the internet, this gave me pause.

On the one hand, as I stated above, if you're running a game like Curse of Strahd, you should probably have a conversation about vampires and about the bleakness of the setting. If you're playing Phandelver and Below, maybe you should have a conversation about character transformation, but these elements aren't immediately apparent from the beginning of the module - it's a secret for the characters to discover. Divulging the involvement of the mind flayers and the Far Realm in a Session 0 before the campaign starts is a "spoiler" of things to come in the adventure.

And what about DMs running custom sandboxes, who might not know every detail of their setting during Session 0? Should DMs have these conversations with players mid-game as their world takes shape? "Oh, I just rolled up a mind flayer in this ruin - better have the Mind Flayer Talk with my players."

The introduction to Phandelver and Below goes on to say that "Given the significance of some of these [transformations], it's better for the player to give you suggestions regarding a change than vice versa" and "[The transformations are] intended to be fun, not to make players uncomfortable". Well, that doesn't sound very horrific.

It's a good thing that Wizards of the Coast is beginning to address consent in their publications, but these issues should be discussed in the Player's Handbook rather than in individual adventures. D&D is a game which includes a lot of violence, death, and other debilitating things that can happen to a character, none of which require player or character consent in the moment. A ghoul might paralyze and devour your character, all while they're unable to fight back. A demon might possess them and make them do all sorts of abhorrent things. A number of creatures can mind control the character and make them into mindless thralls. And yes, creatures like mind flayers, slaads, and others can permanently transform a character into an NPC monster under the DM's control. If the PHB makes the players aware of these possibilities as they learn about the game, its assumptions, and tropes, they are then consenting to any ill fates that may befall their characters by agreeing to play the game.

Solutions will differ by table. Unfortunately, because consent is now an issue in the broader culture war - and safety tools an issue in the more narrow culture war specific to TTRPGs - any nuanced, public discussion of it is virtually impossible. As I said earlier, horror is inherent to D&D in some way, and I make an effort to make my players aware that I'm bringing that assumption to my games.

Players should understand what kind of game D&D is generally as well as the way the DM intends to run it specifically. The DM should include content warnings that body horror, mind control, and possession - among other things - are on the table, just as they should talk about character death, house rules, expected player behaviors, and touchy subjects like colonialism, politics, racism, religion, sex, slavery, etc. Players should be made aware that they can withdraw consent at any time with an out-of-game discussion with the DM or with the use of something akin to X cards in-game, but the DM shouldn't feel compelled to make the game something that it isn't because the players can't handle bad things happening to their characters.

Ultimately, D&D is a game, and DM and players alike are probably both trying to have fun. All kinds of elements of the game might be more or less fun for both DM and players. Those issues are best addressed in Session 0, but can also be addressed in-game at any point.

What makes a game truly thrilling is the triumph made possible by the chance of failure. In D&D that might mean bungling a quest, but it also might mean losing a character, whether by death, transformation, or any number of horrible fates, all of which are heightened in a game with an emphasis on horror. If the DM or players aren't comfortable enough with one another - or unwilling to have the conversations or use the tools necessary to establish comfort - then maybe horror - or D&D, a game ripe with risks to their character - isn't right for them.

Happy Halloween!

No comments:

Post a Comment